Lake Look - Where's the Beach?

How High Lake Levels Impact Shoreline Habitat

OCTOBER 2023

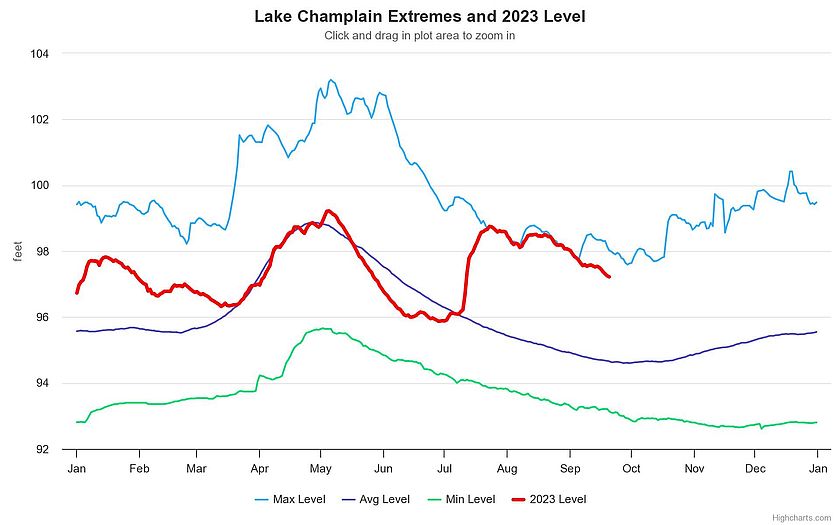

If you have been to a beach on Lake Champlain any time since the Summer 2023 floods, you’ve probably noticed less of what you went there for: the beach. Water levels are still unseasonably high and shoreline areas that are usually dry are inundated from the floods and the consistent subsequent rain we’ve received. The average lake level for September in a typical year is just below 95 ft, and in 2023 it was over 97 ft. A difference of just over two feet may not sound too consequential, but it can have a range of significant shoreline impacts.

Historically, lake level fluctuations over the course of a year followed a simple hill of a curve: levels would increase from a bit over 95 ft. in April, peak in May around 98 to 99 ft., and decline over the summer to the 95 ft. range in the fall, where a small increase in lake level could be seen. This pattern was caused by seasonal snowmelt in the spring, evaporation from summer heat, and then decreased evaporation from cooler, wetter autumn weather.

This pattern shifted in the 21st century. The summer decline started to be disrupted by spikes in lake level in the middle of the summer, close to the high levels we see in May. This does not happen every year, but is a trend we have been seeing more and more since 2008 and is particularly evident this year from the summer floods. Even though you might imagine warmer temperatures from climate change would cause more evaporation in the summer and therefore greater declines in water level, the increased mid-summer rain we’ve been seeing beats this out and raises the lake waters significantly.

With smaller beach area, popular spots become more and more crowded. It’s not just a recreation problem: plants that have adapted to the shores of Lake Champlain for the past several thousand years are not used to this pattern of water level change. According to Aaron Marcus, botanist with the Vermont Department of Fish and Wildlife, there are unique and even globally rare plants that grow in the dunes of Lake Champlain. Beach pea (Lathyrus japonicus) and Champlain Dunegrass (Ammophila champlainensis) are two that survived the transition from the saltwater Champlain Sea to the current freshwater Lake Champlain 10,000 years ago and are found only in rare dunes of Lake Champlain. With the protection of the Alburgh Dunes in the 1990s, these plants were starting to rebound from previous habitat degradation.

This heartening trend shifted in 2011 in the wake of Hurricane Irene, when populations of Champlain dunegrass and beach pea along Lake Champlain’s shores were reduced by about 50% from the extreme flooding. Much of this was the loss of habitat not just from the beaches being underwater, but also from the subsequent erosion of the shoreline. Shorelines with natural vegetation that stabilize the soil are all too rare along Lake Champlain, and cleared shorelines contribute 18 times more sediment deposits than their wooded counterparts do. That is why, according to Wisconsin limnologist Steven Carpenter, riparian vegetation to reduce erosion is the “number one way to build resilience to climate change for lakes”.

Luckily for the beach pea and Champlain dunegrass, the Summer 2023 floods did not trigger the same dramatic lake flooding that Hurricane Irene did and populations seem to be stable in the wake of the high waters. There are more dramatic impacts on the rare plants that grow along rivers throughout the Lake Champlain Basin. However, according to Vermont state botanist Grace Glynn, there is still concern for these and other rare lakeshore plant species, “[…] because these flooding events are causing unprecedented erosion of sandy lakeshores. We’re seeing more and more stone riprap along the lakeshore, which eliminates habitat for these rare plants.” On top of that, the true impact of the floods on certain plant species cannot be understood until at least next year—the floods caused stress and sent some species to seed early, so population changes like that will be evident in 2024.

Wrights spikerush (Eleocharis diandra) is a globally rare plant—they have only been recorded at 20 sites around the world. Among those sites are popular beachgoer spots along Lake Champlain’s Vermont shoreline including North Beach and Leddy Beach in Burlington, Niquette Bay State Park in Colchester, and Alburgh Dunes State Park in Alburgh. The plant is a small tufted sedge that prefers dry summers. In 2016, a dry year with below average lake levels from May to December, the plant had a population boom at its few known sites as more beach habitat opened up with the receded waters. It can seem contradictory, but our changing climate is trending toward a pattern that is not quite as simple as “rainier summers.” Climate change increases the volatility of precipitation patterns in the region and can cause floods or droughts, and because of shifts in the water cycle, different regions of the watershed can experience different climate impacts This can make predicting the future of species that rely on certain precipitation regimen difficult.

“We’re not quite sure how [Wright’s spikerush and other annual lakeshore plant species] will respond to climate change in the long run. We have many rare native annuals along our beaches, and this summer almost all of their habitat is underwater. The summer flooding is problematic because the plants die just when they’re beginning to germinate and flower,” says Glynn. Wright’s spikerush seeds can lie dormant under lakes for decades, so they have a high capacity for resilience, but the question of how resilient they must be to adapt to wetter and wetter summers remains—for them and for us.

Lake Look is a monthly natural history column produced by the Lake Champlain Committee (LCC). Formed in 1963, LCC is a bi-state nonprofit that uses science-based advocacy, education, and collaborative action to protect and restore water quality, safeguard natural habitats, foster stewardship, and ensure recreational access. You can join, renew your membership, make a special donation, or volunteer to further our work.