Lake Look: Native Mussels—Low on the Food Chain, High on the Protection List

February 2021

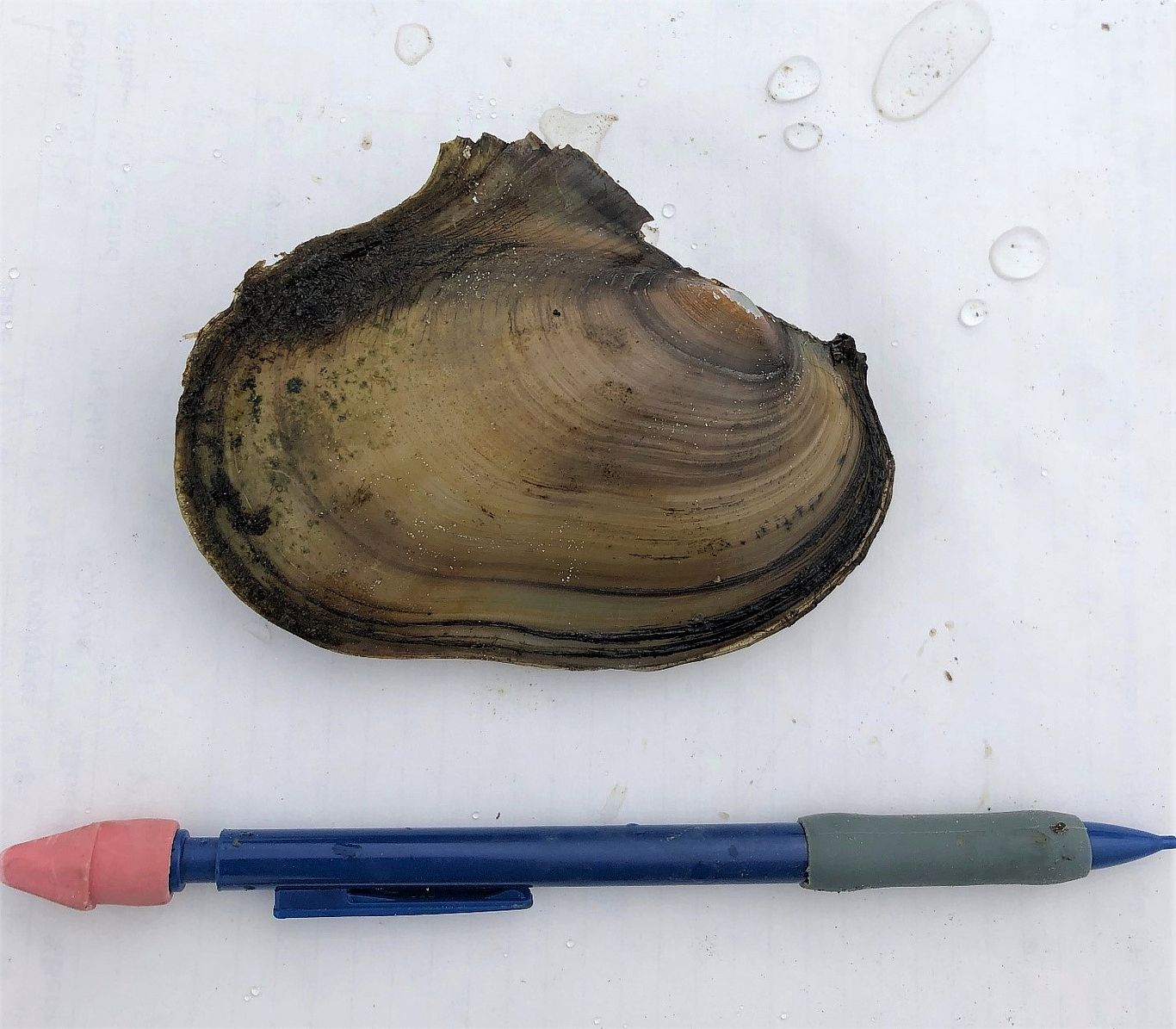

If you’ve paddled, taken a swim, or cast a fishing line in the waterbodies of the Lake Champlain Basin, you’ve likely spent time among one of the most enigmatic and imperiled groups of aquatic animals in our region: native freshwater mussels. They’re quirky—sporting hatchet-like shells and traveling by a single fleshy foot, yet familiar—related to the invasive zebra mussel and edible bivalves such as scallops.

Conservation Status

We care about the survival of native freshwater mussels because they play an essential role in freshwater ecosystems. Issues such as habitat loss (alteration, conversion, fragmentation), sedimentation, and invasion by exotic species threaten our local native mussel populations. These organisms provide biodiversity to aquatic communities, play a key role as filter feeders at the bottom of the food chain, and serve as bioindicators of water quality. To put the rarity of Vermont’s mussels in perspective, 15 of the 18 native species are very rare, rare, or uncommon. According to the New York Natural Heritage Program, “Of the 50 freshwater mussel species known to occur or have occurred in New York, 13 have only historical records, five species are state-listed as endangered, three species are state-listed as threatened, and an additional 15 species have been designated Species of Greatest Conservation Need by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation.”

Natural History

Freshwater mussels have an extraordinary life cycle. Sperm are released from male mussels and siphoned in by female mussels, where the eggs are fertilized. The eggs develop into microscopic larvae, called glochidia, which are released into the water, where they attach to the gills or fins of fish—this is the parasitic stage of their life cycle. Each mussel species has a specific fish host or hosts. For example, the fish hosts for Lake Champlain’s most common mussel species, Eastern elliptio, include yellow perch, smallmouth bass, largemouth bass, chain pickerel, and sunfish. The glochidia develop into juveniles on their fish hosts, then drop off and settle on lake or river bottom sediments, where they develop into adults. Because of this host-parasite relationship, the health of Lake Champlain’s fish populations impacts the health of native freshwater mussel populations.

Though mussels occupy a small amount of space, they are mighty filter feeders. They draw water into their gills through an incurrent siphon, pulling water in, filtering pollutants, and feeding on organisms like phytoplankton and zooplankton (tiny plants and animals). Then they release the filtered water through an excurrent siphon—think turkey baster. Mussels travel horizontally and vertically on lake and river bottoms via a single muscular “foot,” leaving an incised trail in their wake; if you follow the curved paths in the sediment, you’ll likely observe a mussel buried at the endpoint. In the spring, it is thought that mussels may move up in the sediment to aid in reproduction—some mussels have fish-like lures to attract fish for the host-parasite and dispersal phase of their life cycle. Mussels may burrow deeper within lake and river bottom substrates to stay warm in winter or to avoid being washed away during flood events. If mussels don’t make this seasonal vertical migration in shallow waters, they risk being frozen solid or into mobile ice cover.

Project History

Scientists were spurred to take protective action because of the imperiled status of many native freshwater mussel species in the Lake Champlain Basin, paired with the unique role they play in freshwater ecosystems. The genesis of conducting freshwater mussel inventories was based on the conservation priorities established in the non-regulatory 2015 Vermont Wildlife Action Plan and was supported by grant dollars from the state. The Lake Champlain Committee (LCC), Arrowwood Environmental (AE), and the Vermont Chapter of The Nature Conservancy began freshwater mussel survey work in 2018 on the Lamoille and Poultney Rivers in Vermont. Subsequently, the lack of widespread information about native mussel population distribution, abundance, and health in northern Lake Champlain created an opportunity for scientists to bridge this significant information gap. Thus, an LCC and AE field team began to close this gap in 2020 by studying the impacts of non-native and invasive zebra mussels on native freshwater mussel communities in northern Lake Champlain.

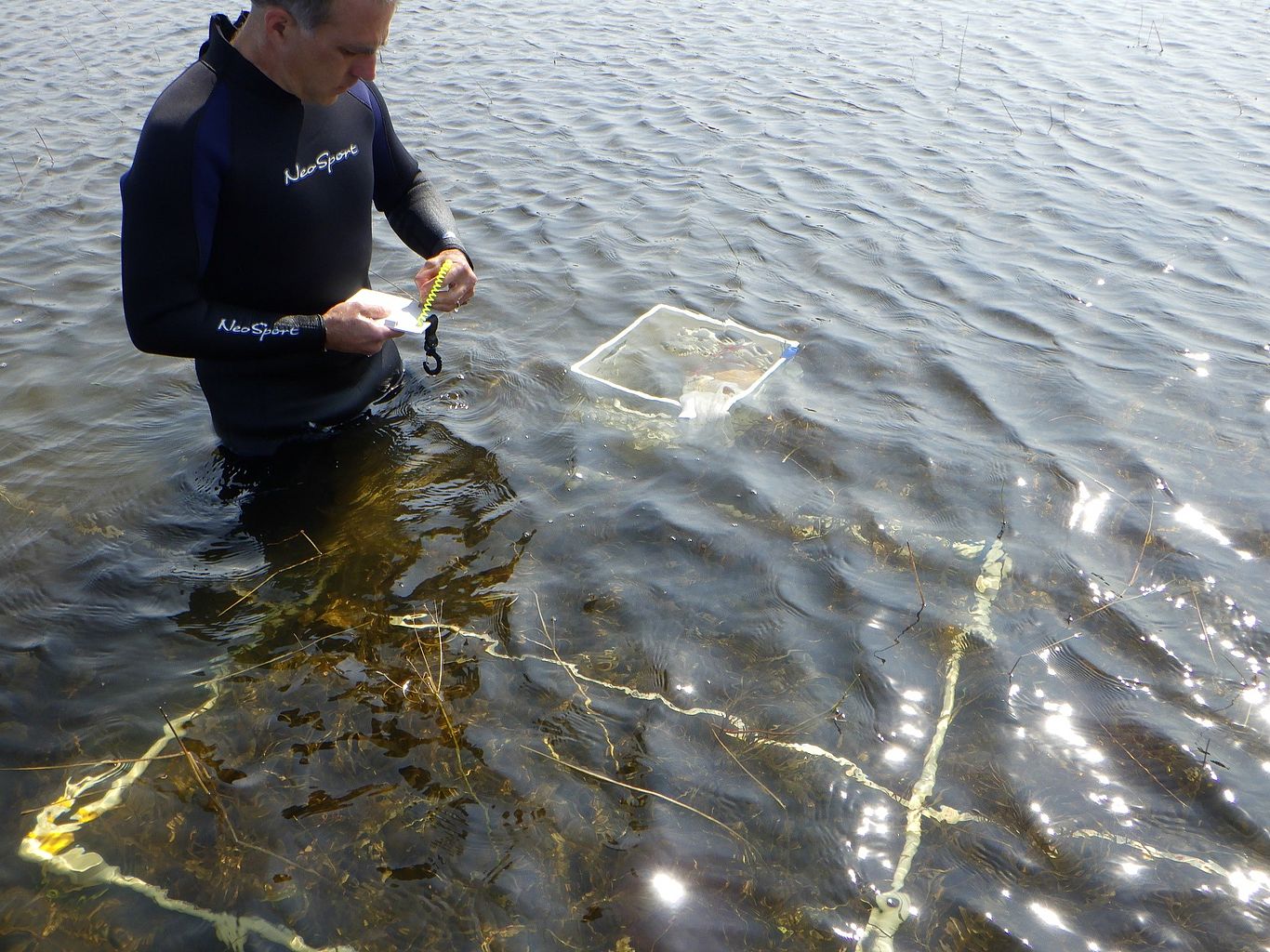

While invasive zebra mussels seriously threaten native freshwater mussels in the southern lake, their impact on populations in the northern lake is unclear. Between July and September of 2020, scientists from LCC and AE assessed impacts to native mussels in Lake Champlain, spanning from St. Albans Bay south to Malletts Bay. This project is a critical part of the conservation process to ensure that the lake’s biodiversity remains intact. The study focused on nine of the 18 species found in Vermont; the other nine species are located outside of the study area: Lake Champlain’s tributaries or the Connecticut River Basin.

2020 Field Work & Results

Donning wetsuits, snorkels, and scuba gear, the field team explored the lake bottom at 38 separate sites, identified and measured over 1,700 native mussels, and counted more than 10,000 zebra mussels attached to the shells of live native mussels. The data showed that sites in Malletts Bay have lower zebra mussel infestation rates than sites in the Northeast Arm and St. Albans Bay. Sites in northeastern St. Albans Bay exhibited high levels of infestation, while sites near the Lamoille River delta showed low or no infestation.

One of the goals of the project was to determine if there were locations in the study area that could serve as native mussel refugia—places where the organisms can survive despite challenging circumstances, such as zebra mussel infestation and climate change. Refugia are essential to the long-term survival of rare, threatened, and endangered species. The literature states that factors such as the influx of calcium-poor water and water currents can limit the dispersal of zebra mussel veligers (larvae), and appear to create areas where zebra mussel adults either do not become readily established or do not thrive. “Other large river systems in the Lake Champlain Basin may serve this function and warrant investigation, especially north of St. Albans Bay, to identify and assess mussel refugia and therefore protect this important part of our freshwater ecosystems,” said Michael Lew-Smith of Arrowwood Environmental.

Native freshwater mussels play an integral role in the health of the waterbodies that we swim in, fish in, and rely on for drinking water. Mussels are humble organisms with a huge impact—they filter polluted water and serve as champions of Lake Champlain’s biodiversity. Learning about native mussels and supporting conservation efforts is a win-win for people and the health of the Lake Champlain Basin’s waters.

Resources

To learn more about native freshwater mussels you can:

1) View species profiles via The Vermont Freshwater Mussel Atlas, a project of The Vermont Center for Ecostudies;

2) listen to the Vermont Public Radio’s Outdoor Radio episode, Invasive Zebra Mussels; and

3) watch the Vermont PBS Outdoor Journal episode, Vermont’s Native Mussels.

Funding & Support

We extend a huge thank you to the Winooski Valley Park District as a key project facilitator, as well as the Lake Champlain Basin Program (LCBP) and New England Interstate Water Pollution Control Commission (NEIWPCC) for funding assistance. Support was also provided in part by the Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation.

Lake Look is a monthly natural history column produced by the Lake Champlain Committee (LCC). Formed in 1963, LCC is a bi-state nonprofit that uses science-based advocacy, education, and collaborative action to protect and restore water quality, safeguard natural habitats, foster stewardship, and ensure recreational access. You can join, renew your membership, make a special donation, or volunteer to further our work.