Nature Note – Lake Champlain’s Snow Globe

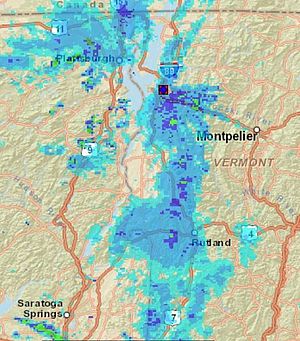

Bands of lake-effect snow over the Lake Champlain region on Jan. 16, 2020 at 4:00 PM. Radar data map courtesy of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

While the sun shines on Montpelier, it could be dumping snow 50 miles southwest in Cornwall, VT. Apart from major snowstorms, namely Nor’easters and “Alberta Clippers,” the formation of lake-effect snow over Lake Champlain is one of the many weather patterns that turns the Champlain Valley into a winter wonderland. Lake-effect snows occur under conditions where the presence of a lake is required. This weather phenomenon is also common on other large lakes such as the Finger Lakes of New York and the Great Lakes. Whether the snow makes you jump for joy or want to escape to warmer realms, it’s a staple of the winter experience in Vermont and New York.

Three conditions prime the pump for lake-effect snow. First, a mass of cold air, usually from Canada, must move over a body of comparatively warmer water. Second, the difference in temperature between the air of the upper atmosphere (between 2,000 and 16,000 feet) and the water must be high (59 degrees Fahrenheit is an approximate minimum temperature difference). Third, the cold air mass and the warm water mass must stay in contact with one another long enough for the air to absorb warmth and moisture.

On Lake Champlain, wind direction and lake width are limiting factors for lake-effect snows. Since Lake Champlain is a north-south oriented lake that is 120 miles long, northerly winds are the only winds that stay in contact with the lake long enough to generate lake-effect snow. The lake’s greatest east-west distance, 12 miles between Port Kent, NY and Burlington, VT, is too short for this weather phenomenon to generate snow. Lake-effect snow is most likely to take place in Addison County, VT, where wind blowing from the Richelieu River hits land near Otter Creek.

Lake-effect snow is typically most intense near the shore. As warm moist air hits land, it slows down because the land has greater friction than the lake water. Wind continues to hit the land and has nowhere to go but up. The air rises to the cooler upper atmosphere. As the water in the air cools, it condenses, forming snow. Lake-effect snow bands typically produce two to three inches of snow per hour.

The Champlain Valley last experienced strong lake-effect snow showers on January 16, 2020. According to Robert Haynes at the National Weather Service, Burlington, “After an arctic front pushed south overnight, snow showers moved into the region and transitioned into several lake-effect bands during the afternoon. Bands of lake effect gradually dissipated over the course of the day.” Six instances of weaker lake-effect bands occurred between November 16, 2019 and February 20, 2020. Experiencing these storms is worthy of any bucket list.

Curious about other lake phenomena like how long parallel streaks of foam form on the water surface or why pockmarks exist on the lake bottom? Check out LCC’s award-winning book Lake Champlain: A Natural History.