What the Muck of Walden Pond Tells Us About Our Planet

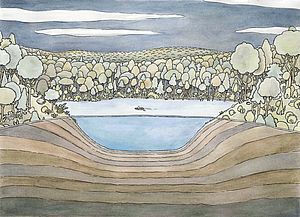

Centuries of sediments deposited on the pond made famous by Thoreau tells a story of pollution and climate change. Illustration from Curt Stager's forthcoming book “Still Waters: The Secret Lives of Lakes.” Illustration by Kevin Hooyman.

Walden Pond is a 62-acre kettle pond in sand and gravel that formed around a block of melting glacial ice about 15,000 years ago. It was here that Thoreau produced one of the first maps of an American lake bed by lowering a weighted line through winter ice. He measured a depth of 102 feet in the western basin, demonstrating that the pond was not bottomless, as local residents had claimed. (In fact, it is one of the deepest in Massachusetts.) Thoreau also recognized that Walden could be both a window and a mirror. He called it "Earth's eye," in which we can see ourselves and our world reflected. In 2015, Curt Stager, ecologist, paleoclimatologist, science journalist, and professor of natural sciences at Paul Smith's College and two students lowered weighted plastic tubes through 45 feet of water near the center of Walden Pond and hauled up several sediment cores. The longest, measuring two feet, captured 1,500 years of environmental history. The story of Walden can be "read" in its muck. Nutrient enrichment, cesium-137 from thermonuclear fallout, the fish-killing pesticide rotenone, an alga linked to climate change, all can be traced. And "the ecological changes revealed in the sediments of the last century were more extreme than anything in the previous 1,400 years," Stager writes in this piece in the New York Times.