Thank you for signing up to receive the Lake Champlain Committee (LCC) Cyanobacteria monitoring reports! Monitoring began the week of June 15 and will run through early fall. Each week we’ll send you an update about conditions monitors are finding on Lake Champlain and at select inland Vermont lakes. This week’s report covers results from Sunday, June 15 through Saturday, June 21, 2025. If you’d like to learn more about cyanobacteria or join our monitoring team please sign up here. We will also hold informational sessions about how to recognize cyanobacteria later in the summer, so stay tuned. Read...

LCC News

At what point does a waterway stop being a river and become part of Lake Champlain? This transition happens gradually in a zone called a river delta where a river empties into the lake. Read...

Join the Lake Champlain Committee at the Pt. Au Roche Nature Center on Sunday, June 8 from 10 AM - 12 PM for an educational training on aquatic invasive species! Learn what invasive species are, why they are a problem, how to prevent their introduction and spread, and how to identify key species in Lake Champlain. Read...

Join LCC and the Northeast Disabled Athletics Association, South Hero Land Trust, and North Branch Nature Center on Thursday, 7/17/2025 between 10:00 AM and 2:00 PM at the Sandbar State Park in Milton, VT. This adaptive kayaking series is an opportunity for community members who want to learn about kayaking or get back out on the water, but can’t use a standard kayak, to use an adaptive kayak with support. LCC will have materials on native and invasive aquatic species, interactive plant identification activities, and information on our Lake Champlain Paddler's Trail.

Pre-registration required. Contact Cathy Webster of NDAA’s Adaptive Kayaking program for more info and to register. Kayak@DisabledAthletics.org | 802-355-8833. Read...

As we gear up for another field season at the Lake Champlain Committee (LCC), we're seeking volunteers for the Champlain Aquatic invasive Monitoring Program—CHAMP! Now entering our third season of CHAMP, LCC recruits, trains, and supports volunteers to survey for aquatic invasive species (AIS) at sites throughout Lake Champlain. As a volunteer, you'll paddle or walk along a shoreline site, rake in samples of aquatic life, assess what you’ve gathered, and report your findings of key target invasive species to LCC via an online form. Read...

Our beloved aquatic creatures share oxygen, food, and habitat —but unfortunately, they also share the water with something far less natural: our trash. A shampoo bottle floating in the lake, an abandoned boat, or a buoy washed up on a beach are all examples of what we call “marine debris.” Read...

Join LCC and our partners in the Marine Debris Coalition for a cleanup of the Burlington Waterfront! Sign up for one of two cleanup locations: the Lake Champlain Community Sailing Center and the Burlington Community Boathouse Marina from 9:00 AM - 10:30 AM. Then join us to sort and catalogue the debris in front of Burlington City Hall during the Church Street Marketplace Earth Day Celebration. Show your love for Lake Champlain and its public access areas by RSVP-ing through the link provided.

Thanks to our partners: the Rozalia Project, Lake Champlain Sea Grant, Water Resources Institute, Conservation Law Foundation, the Burlington Community Boathouse, and the Lake George Association. Read...

Imagine a world where homes are built of glass—not by human hands, but by nature’s tiniest architects. These microscopic wonders, known as diatoms, are a type of single-celled algae that inhabit nearly every aquatic environment on Earth. Their unique biology makes them invaluable contributors to aquatic ecosystems and, surprisingly, to our daily lives. Read...

Lake Champlain has played a central role in LCC’s new Executive Director Jenny Patterson’s life. The lake was a formative part of her childhood, and just as the Little Chazy River flows into Champlain’s waters, she has come back to this cherished spot and is ready to dive in. Read...

Beavers (Castor canadensis) are similar to many humans when it comes to weathering winter: they don’t hibernate, but they spend a lot of their time cozied up in their lodges. Ever the industrious species, North America’s largest rodent will spend most of the autumn season preparing their winter residence. In early fall, after the framework of a dam has been established, a beaver family will transition their ongoing work schedule to constructing their lodge. Read on for more on the schematics of a beaver lodge and beaver activity in the winter and early spring: Read...

March’s snowmelt reveals some unpleasant remnants from the winter season. Pet owners throughout the winter may be tempted to leave their dog’s waste under the snow and ice—after all, what could be the harm of just a few droppings?

As it turns out, these little heaps are not as innocent as the pampered pets that leave them. Canine feces are full of bacteria - the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates that just 100 dogs over two or three days could contribute enough poop to temporarily close a bay and adjacent watershed areas within 20 miles to swimming or shell fishing. This doesn’t just refer to dog dung on the beach – it’s the residue that washes down the storm drain from streets, sidewalks, lawns and other land surface. Read...

When temperatures drop low enough to freeze wide stretches of Lake Champlain, the landscape takes on a new character. Ice replaces rolling waves, creating a surface that invites exploration—whether by skaters gliding across its glassy expanse or anglers setting up for the season. Beneath the frozen surface, life continues, with some species thriving in the cold while others slow down. Read...

It’s a familiar winter symphony in the Lake Champlain basin: snow, ice, and coarse rock salt crunch beneath your boots as you walk down the pavement. However, below the caked layers of snow, a quieter crisis is unfolding. Spreading road salt in pursuit of safer roads and sidewalks produces a cascade of unintended consequences that persist long after winter is over, corroding bridges, damaging roads, and compromising water systems.

Seeing road salt and other additives being spread on winter roads is nothing new. Yet it raises an important question: why can’t we put our roads on a low-sodium diet? Read...

The Lake Champlain Committee (LCC) is extremely pleased to announce the appointment of Jenny Patterson as its new Executive Director. During the summer and fall of 2024, the LCC Board conducted a comprehensive search for a new Executive Director to carry on the legacy of Lori Fisher, who retired on December 31, 2024, after an exemplary career spanning nearly four decades with LCC. Jenny assumed the Executive Director role on January 1, 2025, and will lead the organization’s mission to protect Lake Champlain’s environmental integrity and recreational resources. Read...

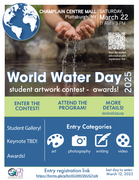

Join LCC at the World Water Day celebration!

March 22, 2025 is World Water Day, and LCC and our Champlain Basin Education Initiative partners are hosting a celebration at the Champlain Centre Mall in Plattsburgh, NY. All are welcome to attend, and K-12 students throughout the Lake Champlain Basin are invited to participate in a contest where awards are given for several categories of creative arts. Read...

While the sun shines in Montpelier, snow could be dumping from the clouds 50 miles southwest in Cornwall, VT. Apart from major snowstorms—namely Nor’easters—the formation of lake-effect snow over Lake Champlain is one of the weather patterns that turns the Champlain Valley into a winter wonderland. Lake-effect snows requires a big lake. This weather phenomenon is also common on the Great Lakes and New York’s Finger Lakes. Whether the snow makes you jump for joy or want to escape to warmer realms, it’s a staple of the winter experience in the Champlain watershed. Read...

Road salt has ripple effects on aquatic ecology, human health, and infrastructure. Anti-icing—the practice of preparing your roads before a freeze rather than salting your roads after ice—helps keep your driveway safe while using significantly less salt. Anti-icing before a storm is similar to using a non-stick spray on a pan before cooking: just as the spray prevents food from bonding to the pan, anti-icing prevents snow and ice from bonding to the pavement so that it can be plowed away. This approach can help you cut salt application in half. The steps outlined below, adapted from New Hampshire’s Best Management Practices for anti-icing by Axiomatic and from The Conservation Foundation, will help you take this approach at home and cut back on salt. Read...

In stressful times, one may envy a turtle: built-in safety from predators with their shells and free from modern expectations of speed and efficiency. Spending summers lounging on logs and rocks warmed by the sun and winters in seemingly peaceful hibernation. However, the winter months present survival obstacles for all animals in Lake Champlain, and turtles don’t have it easy. While hibernation may seem appealing to those who don’t enjoy the long cold nights of the season, it poses challenges with some surprising solutions. Read...